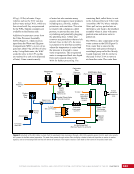

215 DAY IN THE LIFE: EMPTY HOUSE—DECREWING THE INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION CHAPTER 12 left stagnant, microbial growth and chemical changes to the fluid could occur. Think about the drains and water lines of a house that has been sitting vacant for an unknown amount of time. However, the Regenerative ECLSS was designed with multiple recirculation loops internal to processing equipment. These loops were included to allow for start-up transients or failures where the output of the system did not meet quality standards. In these cases, the output would be rerouted back to the input and sent through the system again, in an attempt to continue to further clean the water (see Chapter 19). The ETHOS controllers would periodically use these recirculation loops to move water through the Regenerative ECLSS for the duration of a decrewed configuration. This would keep the system running and prevent stagnant fluid concerns. Prior to decrewing, the crew would install multiple electrical power and thermal cooling jumpers to maximize critical system redundancy. At the time of the Progress 44P accident, the firmware controller for Main Bus Switching Unit (MBSU) (see Chapter 9) 1 was degraded. A jumper would provide power from a pair of parallel internal Direct-Current-to- Direct-Current Converter Units, since this increased the risk of MBSU 1 Emotions on board ran the gamut. Members of the Expedition 27-28 crew were supposed to head home in a couple of weeks, but immediately started hearing rumors of a 2-month extension. Some were happy about having a longer stay, but some had already started thinking about returning to the delights of hot showers, real food, and loving families. I told my family that they would hear a lot of rumors, but don’t expect me home for Thanksgiving, Christmas, or New Years. Although nobody could know for sure, I figured it was better to just set the expectation early for both my family and myself. Meanwhile, the ground team, led by Flight Director Scott Stover, started working the plans for us to prepare the ISS in case we needed to leave it without a crew on board. The ISS is an amazing ship, but it was intended to be operated with a crew to help keep it running and recover critical systems in the event of failures. Our workdays accomplishing the myriad of science objectives became interspersed with just-in-case activities, such as running electrical jumper cables as thick as your forearm to provide a secondary source of power in case a critical electrical component failed (Figure 2). We went about these tasks with the grim realization that we could not protect for every possible thing that could go wrong. Without a crew on board, we were at risk of losing the ISS. While the specialists were working in Houston, Moscow, and around the planet to figure out how to protect the vehicle, we started thinking about how to help prepare the next crew members to be successful when they finally arrived. Our preflight training is very good, but many details associated with living and working on the Space Station are impossible to simulate and train on the ground. Under normal crew rotation schedules, we hand over those “tricks of the trade” during the 2 to 4 months, which we overlap on the ISS. By the time the senior crew departs, the junior crew is ready to take the lead, then train the incoming new crew. Knowing we would not have the benefit of significant (if any) handover training time, we started recording videos to show the new guys how to get the job done. This included a wide variety of activities such as compressing/sealing nasty wet trash bags, cleaning hard-to-access filters, and configuring the confusing pulmonary function test equipment. By the end, we sent down more than 22 hours of instructional videos. In the end, everything worked out very well. The Expedition 27-28 crew returned home with only a 1-week delay. As the Commander of Expedition 29, I knew we were shorthanded for a couple of months however, were ready when the crew of Expedition 29-30 (Dan Burbank, Anton Shkaplerov, and Anatoly Ivanishin) arrived on Soyuz 28. We didn’t sleep much during our 6 days of sharing the ISS, but thanks to the excellent preparation from the ground team and the crew’s dedication to extra training and video reviews, they were ready to take charge as we closed the hatch and headed home. Our homecoming was delayed only a week, and I arrived home to my family just in time for Thanksgiving. And a joyous homecoming it was!

Purchased by unknown, nofirst nolast From: Scampersandbox (scampersandbox.tizrapublisher.com)